Bastiat wake up, they've gone crazy

The French free-trade champion exposed Trump's tariff madness 180 years ago

Economists argue about pretty much everything, but they agree that tariffs are self-defeating. It is a truism that when you raise the price of something, you impose a cost on buyers.

"Liberation day" is not just a huge blow to the US economy: it is above all an assault on common sense. Trump's contention that foreigners are footing the bill flies in the face of the most testable of facts: tariffs are paid by domestic customers and firms.

I've read many excellent rebuttals of the White House's absurdities, but the ubiquitous talk of a "trade war" is unconvincing. A war starts with a country attacking another. Here, the initial damage is inflicted on Americans themselves; foreign sellers do suffer, but indirectly - through reduced demand for their products.

What is going on would be best characterised as "deliberate friendly fire in the hope of inflicting massive collateral damage". Admittedly, this is not nearly as punchy as "trade war". Maybe military metaphors are best avoided in this context.

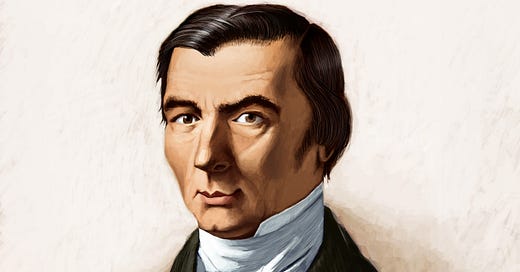

I found the most elegant and eloquent refutation of Trump's trade follies in an article written almost 180 years ago by Frédéric Bastiat. Like his contemporary and fellow liberal MP Alexis de Tocqueville, Bastiat is one of those French geniuses who are widely recognised abroad but had zero influence in their own country.

As a writer, Bastiat is best known for his demolition of protectionist fallacies. He has a much pithier phrase than "deliberate friendly fire in the hope of inflicting massive collateral damage". It is in the title of his 1847 essay "Two losses against one profit".

In that text Bastiat seeks to quantify the harm wrought by tariffs thus: "When a duty raises the price of an object by a given amount, the nation gains that amount once and loses it twice."

He drives home this point by using a model involving French and British knives in an otherwise closed economy. To make it more readily understandable in world of 2025, I will use American and Chinese kitchen utensils.

Say US cutlery makers sell a knife for $3 and the made-in-China equivalent costs $2. To "level the playing field", as Trumpists would put it, a 50% tariff is imposed on the Asian stuff. So US consumers pay $3 for the knife, wherever it comes from.

Who benefits and who loses? US industry gains $1 - not $3, as the other $2 would have been spent on another homemade product: the gain from protection amounts to what is paid over and above the market price.

The buyer of the knife loses $1: for $3 they could have had a Chinese knife plus $1. With that dollar they would have bought a Hershey bar or a Gillette disposable razor. So Walmart and its suppliers also lose $1.

You might say: "Hold on: yes, consumers pay a higher price for the knife, but the extra dollar will support more than the US cutlery maker. It benefits the firm's workers and its suppliers, who will in turn recycle it into the domestic economy. The dollar spurs general activity through successive rounds of spending."

The "multiplier effect" argument has been used by protectionists for over a century – notably by Trump's trade guru Peter Navarro, among others. But Bastiat refuted it long ago. The dollar gained by Walmart under a free-trade regime would benefit its workers too. Whether you spend $3 on a knife, or $2 on the same knife plus $1 on something else, the use of the $3 beyond those transactions is irrelevant. "In both hypotheses [the sums] follow infinite parallels which cannot affect our calculation," Bastiat wrote.

Protectionism thrives on hatred of foreign competition - "the monster on which all economic anger is vented," as Bastiat put it. However, he notes, tariffs ultimately turn citizens of the same country against one another. The main rivals of protected manufacturers are not foreigners, but other domestic producers whose customers "have been legislatively and unjustly taken from them", he notes.

Today's integrated value chains do not invalidate Bastiat's insights. True, the line between domestic and foreign producers is blurred in a globalised economy. But all this means is that even US-based manufacturers are hurt by tariffs. Under Trump's mad bid to bring production home, the gains are more elusive than ever.

To be sure, our world is very different from the one Bastiat lived in. In the 19th century protectionism was the rule. Frédéric Bastiat was fighting a system he regarded as economically and morally indefensible – and in which big powers competed for new markets through conquest (Bastiat was a fervent anti-colonialist).

The 21st century, by contrast, has been shaped by trade liberalisation. The challenge is not to overhaul a flawed order but to preserve one that works. The task might seem straightforward. Unlike Bastiat, who had little more than correct reasoning to offer, his heirs can point to an impressive record: more than a billion people have been lifted out of poverty since 1990; the system has also richly benefited the rich world, notably the US.

But this virtuous framework makes the stakes more daunting for today's free traders. Back then, failure meant missing out on greater wealth creation (the 19th century did experience remarkable development, but through technology not commerce). The risk nowadays is impoverishment on an epic scale. Ever after pausing his worst tariffs, Trump has unleashed the most disruptive policy in the history of global trade - one that threatens to take humanity back to a beggar-and-invade-thy-neighbour world.

America's current bout of populist fervour, like all revolutionary spells, encourages utopianism. The current order, which has the drawback of actually existing and therefore being imperfect, is rejected in favour of an ideal that is by definition flawless. In such times Monty's raw-deal principle applies: "Nonsense has a welcome ring and heroes don't come easily." Bastiat is needed more than ever.