How public broadcasters perish

The BBC and its French counterparts face populist assault. Only one has the neutrality to survive it

It is tough being a public broadcaster these days. As governments squeeze your funding, private competitors poach your audiences and right-wingers question your neutrality, trouble awaits if you put a foot wrong. In Britain and France, where nationalist parties are within reach of power, two incidents illustrate the consequences faced by public media accused of bias.

The BBC has been under fire over a documentary broadcast just before the 2024 US election. The filmmakers spliced together two clips from Donald Trump’s notorious speech on 6 January 2021, suggesting he had told supporters to storm the Capitol. When the edit belatedly came to light last November, the BBC apologised. This pacified neither Trump, who sued, nor Britain’s right-wing press, which sees the corporation as a nest of lefties. Critics asked why nothing had been done about the mistake until it was exposed. By mid-November the BBC’s director general, Tim Davie, and its head of news had resigned.

Across the Channel, the offence involved France Inter, the country’s main public radio station. In October 2023, three weeks after the Hamas killing spree that triggered the Gaza war, one of the comedians hired to spice up news programmes called Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu a “Nazi without a foreskin”. There was outcry. Back on air a few days later, the comedian refused to apologise and sarcastically conceded that Hamas too were “Nazis without foreskins”. In April 2024, after prosecutors rejected hate-speech complaints over the original outburst, he repeated it on air. He was suspended and fired six weeks later.

Although national broadcasters in both countries face similar pressures, what these incidents reveal above all is the vastly different standards to which they are held. The BBC is being punished for an editing error in an otherwise balanced documentary from the prestigious Panorama strand. The two sentences we heard Trump say – “We’re gonna walk down to the Capitol and I’ll be with you (…) and we fight. We fight like hell and if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not gonna have a country anymore” – are a fair summary of his speech. Under the rallying cry “Stop the Steal”, the then-outgoing president had called supporters to the National Mall with the aim of preventing Congress from approving the election results. But the BBC should have clarified that the sentences belonged to different parts of the speech.

The problem, first flagged in an internal report, was not noticed by the public (least of all in the US where the film was never available) until a year after broadcast, when the report was leaked. The BBC’s failure to acknowledge the mistake while executives wrangled over its gravity ultimately cost the bosses their jobs. And the corporation may pay a heavier price still. Trump is seeking up to $10bn in damages for “brazen” election interference.

While the BBC selectively quoted one world leader, France Inter threw an anti-Semitic insult at another. The jibe against Netanyahu drew a warning from the regulator but no retraction or apology from the station. While expressing “unease”, France Inter chief Adèle Van Reeth stood by the comedian. “You don’t fire a humourist over a bad joke,” she declared. “A space for political satire… is the sign of a functioning democracy.” No doubt – but is public radio really an appropriate forum for calling a foreign head of government a Nazi without a foreskin? Management never offered a clear answer.

Even the comedian’s firing was equivocal. Appearing before a parliamentary inquiry on public broadcasting in December, radio bosses made clear that the insult by itself had not been the reason. Van Reeth said that repeating it had only been part of a pattern of disloyalty that included social media posts and disparaging comments about colleagues. Although the parliamentary panel is dominated by right-wing critics, neither she nor the head of Radio France faced any pushback about their handling of the affair, let alone resignation calls. The comedian, meanwhile, is challenging his dismissal in an employment tribunal, citing violation of his freedom of speech and seeking €400,000 in damages.

The gap between the nature of the transgression and the consequences in the two countries – minor for crude reductio ad Hitlerum vs cataclysmic for an unmarked edit – reflects a wider divergence in journalistic culture. The French tend to ingest their news coated in opinion. So do many Brits, of course, hence the success of their tabloids. But sufficient demand for cold facts persists to maintain a press tradition of separation between news and comment. Of course, as the cliché goes, editorial choices always reflect unconscious biases. The operative word here is “unconscious”: all a journalist can do is try to keep their own angle out of the copy. This discipline is drilled into every hack in the UK. In France it is optional. Reporters there operate in a professional environment where wearing your politics on your sleeve is not just tolerated but expected.

The upshot is two fundamentally different models for public broadcasting, despite similar-sounding language. Neutralité - the focus of the French parliamentary inquiry – does not mean “neutrality” in the British sense. A better translation would be “pluralism” or “diversity”. French law mandates “the pluralist expression of currents of thought” for all TV and radio services. The head of France’s broadcasting regulator, Arcom, told the inquiry that neutrality “must be reconciled with editorial freedom and the right to criticism and even parody”. So long as overall balance is respected, journalists in private and public media may opine forcefully - and the chase for audiences encourages them to do so.

Pluralism is a requirement for British broadcasters too. But the BBC goes beyond this legal minimum: on top of ensuring a range of perspectives, it bars in-house journalists and experts from expressing political views in any outlet, including social media. This self-imposed rule is rooted in the idea that a claim on the public purse entails a duty of neutrality. Expecting people to pay you on pain of a criminal record is a big ask. As those forced sponsors come from across the political spectrum, the least the BBC can do is abstain from furthering causes they might oppose.

My contention is that the BBC’s approach to neutrality is vital if state media is to survive as a credible institution. You might object that someone who worked for the BBC for 30 years would say that. But this hopefully makes me a knowledgeable observer, not an apologist. I acknowledge that the corporation is far from perfect: the Panorama edit was one of many problems catalogued in the leaked memo. Davie was the third director general forced out over journalistic lapses in the past 21 years. The BBC doesn’t always live up to its principles. What I’m defending is not so much a record as a model.

French-style pluralism is a recipe for discontent. You cannot import the confrontational culture of modern media into the public-service sphere without angering most of the people most of the time. France’s electorate can be divided into five broad blocs: the hard left, the moderate left, centrists, conservatives and the far right. Under Arcom’s loose representativity rules, a scrupulous channel might rotate various journalists through its opinion segments accordingly. The result: any given slot offends 80% of potential listeners to some degree.

Barbs about circumcision aside, two samples give a flavour of the kind of language used on France Inter without attracting censure (clips added for polyglots who want the full diatribes).

In the first, comedian Charline Vanhoenacker imagines she is the overcoat of conservative leader Laurent Wauquiez, to gales of laughter in the studio of the main morning programme: “Even when I come back from the drycleaner’s, I feel dirty. Sometimes I want him to catch one of his balls in my zipper.”

In the second, commentator Sophia Aram says antisemitism “oozes from every pore” of La France Insoumise, the largest left-wing party. “Antisemites are like paedophiles,” she adds. “They always lurk where they can exercise their vice: paedophiles near kids, antisemites wherever they can call for Israel’s destruction with impunity.”

Depending on your views, you might applaud one of these statements and recoil from the other. But the damage is cumulative. As Vanhoenacker and Aram both lay into the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) as well, between them they manage to antagonise 100% of the electorate.

It would be troubling enough if France Inter was the equal-opportunity offender it claims to be. But it isn’t. Its newsroom comedians target the right-wing opposition much more often than they do the left (leaving aside the governing centrists and their allies: those in power are fair game).

Nor is the imbalance confined to satirical slots. I listened to the Grande Matinale, the four-hour morning programme on France Inter, on two consecutive days in December. The news was dominated by the publication of Journal d’un prisonnier by Nicolas Sarkozy, which went on to be a best-seller. Comment was uniformly negative. Columnist Patrick Cohen focused on Sarkozy’s overtures to the RN, adding drily: “This amounts to implementing what his son Louis has proposed for road traffic: removing all red lights.” Aram and Vanhoenacker, in rare agreement, laid into the book. Another comedian sneered: “This sob story made me bawl my eyes out... Better get the audiobook: reading while crying doesn’t work: tears smudge the words and you can’t see a damn thing.”

Not all segments expressed opinions, but those that did reflected progressive themes. The press review was particularly striking. On one day the focus was “eco-anxiety” among children who had experienced climate disasters such as flooding. The lesson: “We need to take care of our planet to take care of our kids.” The next day’s digest pulled together articles highlighting various forms of male domination: MPs chatting among themselves when women colleagues take the floor; rural women relegated to childcare and low-pay jobs; girls getting less pocket money than boys. In conclusion, the presenter exhorted mothers who work part time to ask their partners for compensation “because your time is not free”. It was a lecture masquerading as a press review.

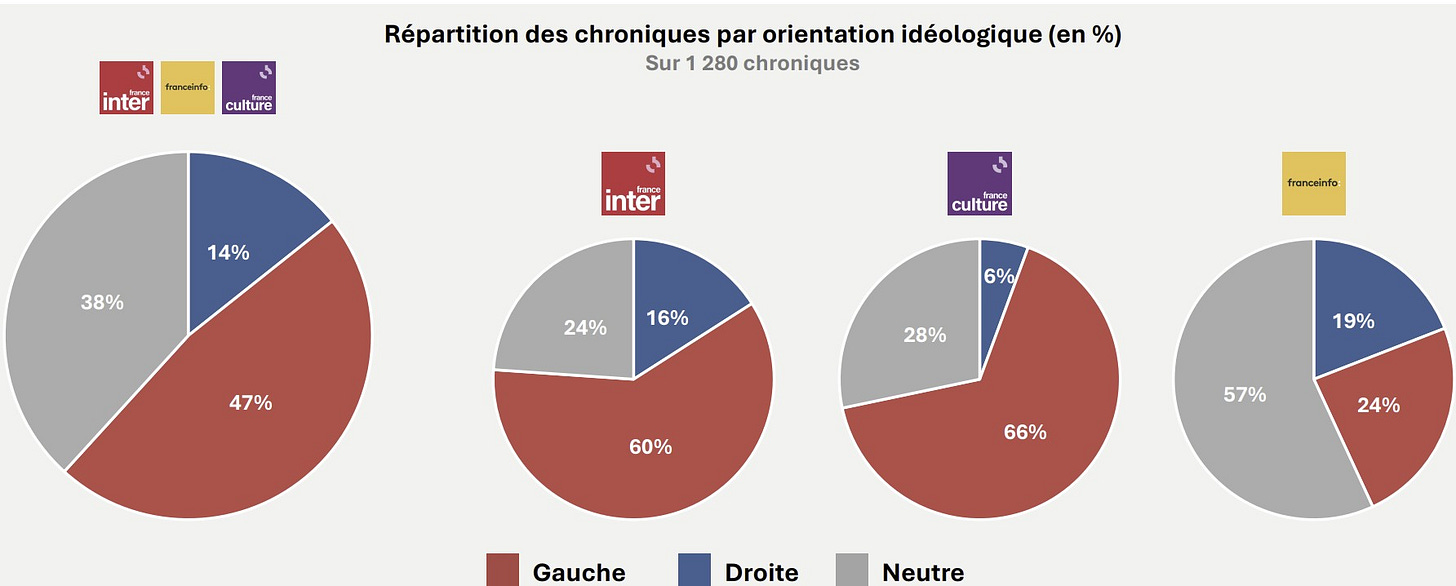

Two mornings of listening prove nothing on their own. But hard data support what anecdotal evidence suggests. The Institut Thomas More, a Paris-based think tank, analysed 200 hours of prime-time morning programming on Radio France stations throughout October 2025. It found, first, that both ends of the political spectrum were underrepresented and got largely negative coverage, particularly the far right. The moderate left got the most favourable treatment of all political groups. Secondly, comment segments were heavily skewed towards the left, notably on France Inter and France Culture (France Info, a news channel, was much more balanced – chart below). The study also found that of 98 topics raised on all three stations, none showed a majority of segments approached from a right-leaning angle, with some subjects (feminism, policing, discrimination) treated almost exclusively from a left-wing perspective.*

A notable form of activism on public airwaves is the critique of right-wing media. It is vital for journalists to hold each other accountable and expose falsehoods. But those who extend the scrutiny from facts to opinions are on slippery ground. Whether a particular worldview distorts coverage can be a matter of interpretation. Criticising the editorial priorities of a competitor is especially tricky for public-service organisations supposed to stay above the political fray. The media empire owned by Vincent Bolloré, a billionaire with staunch conservative views, comes in for relentless attack by public broadcasters over the quality and tone of its journalism. Admittedly, Bolloré outlets also snipe at them just as relentlessly – but this only reinforces the suggestion of payback by state-owned channels.

The attacks on conservative media vary in tone and substance. At the high end is a recent hour-long film on France 2 which mixed legitimate critiques of untruths spread by CNews, Bolloré’s flagship channel, with criticism of its programming choices (platforming far-right figures, highlighting immigration, etc.) At the low end is a France Inter broadside against a female journalist working for a magazine on the “right, right, right, right, right, right, right – really right”, to whom the columnist sends a mock love message: “Little Catholic girls turn me on… When I think of you I dream of Austrian holidays in lederhosen. Let’s play naughty games where you dress as Joan of Arc and I as [far-left leader Jean-Luc] Mélenchon.”

Needless to say, the BBC would not allow such crudeness from a guest, let alone one of its journalists. But it’s important to understand why, fact-checking aside, it refrains from criticising other news organisations. Beyond political neutrality, the concern is commercial fairness. As a tax-funded body, the BBC is open to the charge that its free content can damage rivals that live or die by the audiences they can attract. The answer - the corporation fills gaps in the market and avoids competitive harm - isn’t completely convincing. But at least the need for restraint is recognised.

French public broadcasters feel no such inhibition. Despite substantially higher budgets per employee and the security of state funding, they are losing ground while Bollore’s audiences are rising. CNews recently became France’s top news channel. This superior ability of a private operator to cater to public needs might have given pause to reflect. Instead, state-run channels have intensified their attacks. France Télévisions is even suing Bolloré media, alleging that the denigration it suffers at their hands amounts to commercial harm.

Another little-known safeguard of BBC neutrality is its relationship with trade unions. Those representing staff may negotiate on pay and conditions, but editorial interference is strictly forbidden. In France such meddling is routine. In September the communist-led CGT, the main union within France Télévisions, pilloried star anchor Léa Salamé over her coverage of protests against budget cuts, accusing her of “totally obscuring the reasons for popular anger”. Another major union, CFDT, has issued a booklet advising journalists on how to avoid “falling into the trap of promoting extreme-right ideas” and calling for different treatment of the RN because “it does not share our democratic values.”

In Britain, union instructions on how journalists should cover a specific political party would be unthinkable. So, for that matter, would the hiring of someone like Léa Salamé as a news anchor. She is the partner of Raphaël Glucksmann, a prominent centre-left MEP and potential presidential candidate. Regardless of Salamé’s professionalism, the conflict of interest is apparent. But then in France lines are crossed at every level: partisan journalists on public payrolls, unions seeking to dictate editorial choices, and presenters partnered with politicians. Small wonder that accusations of bias stick.

Defenders of public broadcasters present them as victims of an international campaign by populists. Around Europe, warns Le Monde, “funding for the sector is shrinking while attacks from the extreme right are multiplying”. According to Spain’s El Pais, the far right everywhere threatens “to strangle state-owned media corporations or put them at its service if it comes to power”. True enough, and precedents from Eastern Europe are alarming. The head of the European Digital Media Observatory, a EU-funded body, quoted by El Pais calls public media a “cornerstone of democracy”. Indeed, but a caveat is missing: on condition of genuine neutrality and sound management.

Claiming that public broadcasters are virtuous by nature is a convenient piety. Such circling of wagons dispenses them from taking a hard look at their own practices. Timothy Garton Ash, quoted in the same El Pais article, cites Canada among the countries with a “trusted public broadcaster”. But it is not trusted by most Canadian conservatives, and it’s facile to claim bigotry as the reason. Thoughtful critics have argued that the CBC has abandoned mass appeal for cultural elitism. In 2022 journalist Tara Henley, hardly a right-wing firebrand, publicly resigned from the corporation in protest at editorial priorities that included non-binary Filipinos suffering from a lack of LGBT terminology in Tagalog.

Accusations of metropolitan provincialism levelled at public broadcasters are not all politically motivated. Neither can budget concerns be dismissed outright as attempts to starve critical voices into silence. The question of value for money is particularly valid in France. The BBC gets about €4.24bn in public funding, €61 per capita, about the same as its French peers (€3.95bn; €58 per capita). Workforce levels are comparable too: 21,000 for the BBC, against 17,000. But the gap in reach and efficiency is yawning. On top of dominating its domestic market, the BBC is a global brand, notably through the World Service and its 300 million weekly listeners. The reach of French public broadcasters is relatively low at home (only 28% for under-35s) and negligible abroad.

The BBC has remained a major player despite seeing its annual budget slashed by 30% in real terms over 15 years, deeper cuts than those at France Télévisions. Respective pay levels are good indicators of efficiencies on both sides. The average salary at France Télévisions is €71,500 a year, well above the industry rate. The median wage at the BBC - €60,000 – is near or below market rates depending on the role. And this is despite greater competition for talent: underpaid BBC workers have alternatives to choose from, including US giants (TV networks, major newspapers, Netflix, Amazon, Apple) which maintain large offices in London. France Télévisions faces no such upward pressure on salaries. Bolloré media are notoriously stingy employers.

The BBC is a lean operation with a worldwide audience. French state media combine high costs and narrow appeal. When Le Monde states that even the “venerable” BBC faces the type of challenge that plagues its counterparts in France, the comparison is designed to flatter. A struggling second-division club with a bloated payroll may as well argue in its defence that Manchester United too is beset by injuries, glossing over the fact that the two teams are not in the same league.

Instead of using the BBC as a shield, French public broadcasters would do well to see it as an inspiration. National media are most vulnerable when societies polarise — yet that is when their traditional mission becomes most vital. They must stress shared values when everyone fights for a cause, speak truth when everyone spins, and take responsibility when others point fingers. Even the BBC’s focus on these principles may not save it from the populist ire. For French broadcasters, their blithe indifference to genuine neutrality will lead to irrelevance at best, takeover by the fiercest partisan forces at worst.

* Radio France and others have criticised the Institut Thomas More study for relying on artificial intelligence — yet Radio France itself announced it would use AI to analyse its own content “to make things even more objective”. During Adèle Van Reeth’s recent hearing, a sympathetic panel member brushed aside the findings as coming from a “self-proclaimed liberal and conservative think tank”, attacking the messenger rather than engaging with the message. The institute’s methodology is transparent: AI processes hundreds of hours uniformly, with human review correcting transcription errors and misunderstood irony. The study reveals less political bias that the objections do.