Paris Olympics: Deconstructing the French

During the Games, comment from Britain about the host country was not always cogent

The premise of this newsletter is that foreigners can help you understand your own culture.

But the mere fact that you were born and bred in elsewhere doesn't mean that your opinion on a place is worth having. The perspective from outside can be just as skewed as your own self-image.

My previous post dealt with warped French views on events in Britain. Here I consider distortions in the picture from the reverse angle.

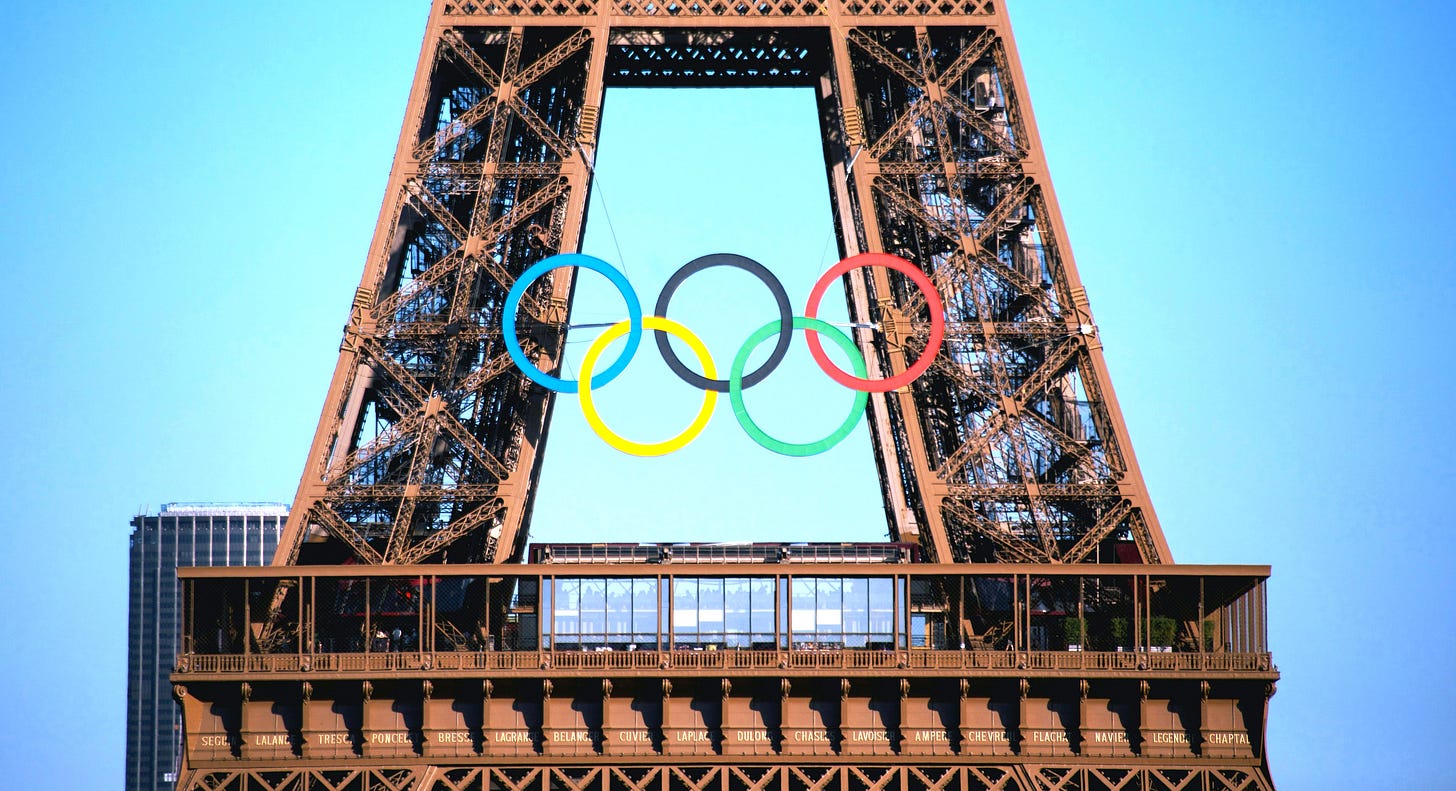

With the world fixated on the Paris Olympics over the past two weeks, there was no shortage of comment on the country. Not all of it was useful. I'll take two examples from the British press last month - after that I stopped reading - not because they were particularly egregious, but on the contrary because they reflect clichés.

The first was an opinion piece entitled "The opening ceremony was beautifully French – you just didn’t get it" (The Daily Telegraph, 27 July).

The author, a UK-based French pundit, takes issue with British commentators who in her view were not as impressed as they should have been by the inaugural extravaganza.

To "explain the essence of Frenchness", she starts with an altercation she once witnessed on a Paris street, as two men exchanged choreographed insults before a good-humoured climbdown. The ceremony, she writes, had the same histrionic quality: "truculent, impudent, not taking itself too seriously, a bit kitsch and over the top, wrenchingly beautiful and moving at times."

The spectacular epitomises "the emotional rollercoaster that being French is – one moment you’re filled with self-hate, the next beaming with national pride." Unlike those British grumps, the French deemed it "an absolute triumph – a much-needed moment of unity for the inner-conflicted nation".

Up to a point. French people did give it a thumbs-up, but not an ovation. According to a poll 44% of those who watched it - a self-selected group – felt it was "very successful", 42% "rather successful"; 12% thought it was either meh or awful.

To call it a celebration of harmony is even more of a stretch. The brain behind the ceremony was Patrick Boucheron, a historian known for his vigorous left-wing views. Far from stressing a common heritage, he emphasised what divides any nation most - politics. He said on the night: "We restored pride in the country not for its identity but for its political project: to go forward, history on the move."

You may agree or disagree with Boucheron, but he's hardly a unifier. There was a lot of fun on display, but it was a globalist sophisticate's idea of fun. The tableaux featuring drag queens and dancers mimicking a bisexual threesome were designed to irk the narrow-minded and the reactionaries. And it worked.

The article may have been written by a native, but it played to British stereotypes about the French. Those outrageous people know how to enjoy themselves! After screaming at each other all day, they gather around the dinner table over good food and even better wine. And, she might have added, they have fantastic sex afterwards.

To be sure, freethinking and hedonism have deep roots in France, but so do traditional values. The country was never progressive over ethical or social issues. It was a late adopter on the vote for women, the death penalty, abortion and LGBT rights. The law on same-sex marriage triggered mass protests. Resistance to assisted dying and surrogacy remains strong. You may regret all this (I, for one, do). But in a country with a strong conservative streak, the Olympic opening hardly an exercise in national communion.

The other boilerplate piece of journalism was 'My heart is broken by France's Olympic hijab ban' (BBC, 25 July).

The standard view in the English-language media is that France is officially Islamophobic: bans on hijabs in schools, sports and public spaces have marginalised Muslims, particularly women, in the name of secularism, universalism and other "Republican values".

As Amnesty International put it: "French authorities have been weaponising these concepts" in a 20-year campaign fuelled by "prejudice, racism and gendered Islamophobia".

It's not surprising that Amnesty should look at everything through the lens of human rights – its core cause - and frame the debate in terms of the usual oppressor-oppressed dichotomy. We can expect private news organisations, from The New York Times to The Daily Telegraph and Sky News, to take similarly stands. But for a public broadcaster with commitment to editorial neutrality to adopt an activist perspective is problematic.

The BBC story quotes French women basketball players who are prevented from wearing hijabs during games. "It's very hypocritical for France to call itself the country of freedom, of human rights, but at the same time not allow Muslims or their citizens to show who they are," says one.

Secularism, an activist says, has been "instrumentalised to erase all differences and more specifically the Muslim identity". The BBC goes on: "As the Paris Olympics make history as the first to achieve numerical gender parity… Muslim French women and girls continue to face barriers on their home turf - which campaigners like Amnesty International say is a 'violation of their human rights' with a 'devastating impact'."

One can sympathise with those who are forced to leave their religious identity in the locker room. France's "Islamist separatism" law – which is mentioned in the piece without explanation – says nothing about sports. As private bodies, individual federations set their own rules. Tennis and handball allow players to wear hijabs. If you find the bans in football and basketball invidious, you're not alone: many in France regard such fatwas as secularism, or laïcité, taken too far.

But Paris 2024 was a special case and the article failed to stress the distinction. The Games were a state event, spearheaded by a Minister for Sports and Olympic and Paralympic Games. A quarter of the funding, €2.45bn, came from the public purse. Regardless of the version of laïcité you support, it's difficult to see how French athletes could have been allowed to advertise their faith while wearing the country's colours. Other competitors, of course, were free to do so.

My criticism is not with the BBC's coverage as a whole. The most cogent comment on the hijab issue came from Hugh Schofield, the BBC's key man in Paris. When asked about laïcité and how it affected the Olympics (on the Sunday programme, 28 July), Schofield said:

"It's not an easy question to answer because the concepts are very French and often evoked in the French language. Conceptually it's a French thing.

"Basically it's the idea that there is something more important than religion, which is citizenship. If you grow up in France, you prize that and it comes ahead of religion. Expressions of religious affiliation should be private and they should not impinge on the public sphere in areas like schools and - in this case - sports."

Schofield pointed out pointed out that Olympic organisers had let a sprinter take part in the opening ceremony wearing a cap with no religious connotations. "There is a bit of give here," he said. "But it's a principle that people outside France do not understand."

I found Schofield's non-judgmental definition of laïcité illuminating. It was comforting to note that foreigners can help you understand your own culture after all.

Intelligent and instructive, this from a Frenchman living across the sea.