The invention of totalitarianism

An exhibition highlights the year when revolutionary Paris terrorised the whole country

This is the third in a series of articles about my native Paris. The first was a personal view of how the city has changed since I left. The second focused on a medieval mayor whose resistance to state absolutism has been forgotten – and God knows champions of liberty need to be remembered these days!

The third instalment below recalls a darker episode in the city's history. The Terror marked the hijacking of the French Revolution by Parisian ideologues. This article is a slightly longer version of a piece published by the Times Literary Supplement on 6 February. It refers to an exhibition that has now ended but whose lessons are timeless.

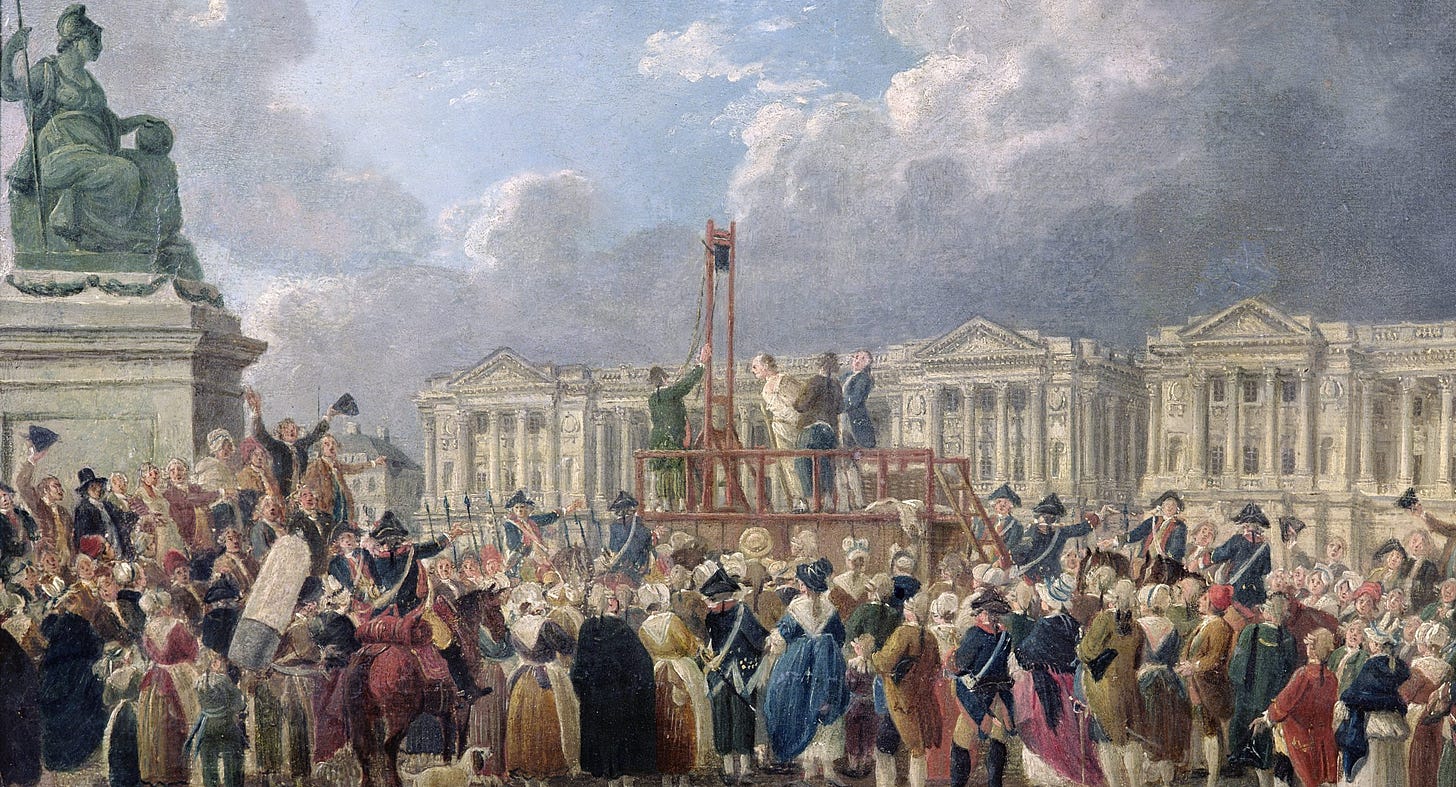

Nicolas Froidure was a true revolutionary. A clerk working for the Paris prosecutor, he organised a militia before the storming of the Bastille in July 1789. Later, as an officer in the city’s police force, he rounded up enemies of the people. But by mid-1794 the ruling Committee of Public Safety was suspicious of any independent power. Froidure and other Paris police chiefs were accused of plotting to kill the committee’s supremo, Maximilien Robespierre. They were detained alongside people they had hunted. On June 17, Froidure faced the revolutionary tribunal and was guillotined. He was twenty-nine.

All that is left of Froidure’s short life is a medallion with his portrait and a lock of hair kept at the Musée Carnavalet, the museum of the capital’s history. It features in a remarkable exhibition, Paris 1793-1794, which documents the paroxysmal stage of the French Revolution, known as the Terror.

The Musée Carnavalet is the ideal venue for such an event: during the Terror, Paris wrested control of the revolution from the rest of the country. In July 1789, as the absolutist ancien regime crumbled, it established its own administration. The new commune de Paris was divided into forty-eight sections dominated by craftsmen and shopkeepers. In the cauldron of radicalism that was Paris, this vanguard resented the influence of provincial moderates who held sway over the legislative assembly.

In 1792, as the exhibition catalogue says, the sections “become a focus for activism by a new type of citizens, the sans-culottes”, who stormed the king’s Tuileries Palace and massacred hundreds of royalist suspects in prisons. Legislators got the message: a new assembly, the Convention, abolished the constitutional monarchy, set up only the previous year. In control of the city, the insurgents now pressed the Convention to adopt their agenda “through the threat of violence if necessary”, the museum’s historians write. A sans-culotte leader is quoted as saying: "The revolution takes place in Paris, therefore Paris decides."

The emblematic figure of the time, Georges Danton, a key member of the Committee of Public Safety, wanted a draconian state in order to forestall mob rule. The political use of the word “terror” first emerged in that context. "Let us be terrible to spare the people from being so," he said. ("Soyons terribles pour éviter au peuple de l'être.")

The Convention was divided between the majority Girondin faction, who were strong in the provinces and hostile to Parisian militancy, and hard-line Montagnards. Amid hunger and conflict – France had disastrously declared war on the Habsburg Empire – tension reached boiling point in May 1793: the sans-culottes stormed the Convention and purged the Girondins. Robespierre and other Montagnards seized the Committee of Public Safety in July. Danton stepped aside, and thus began the Terror proper.

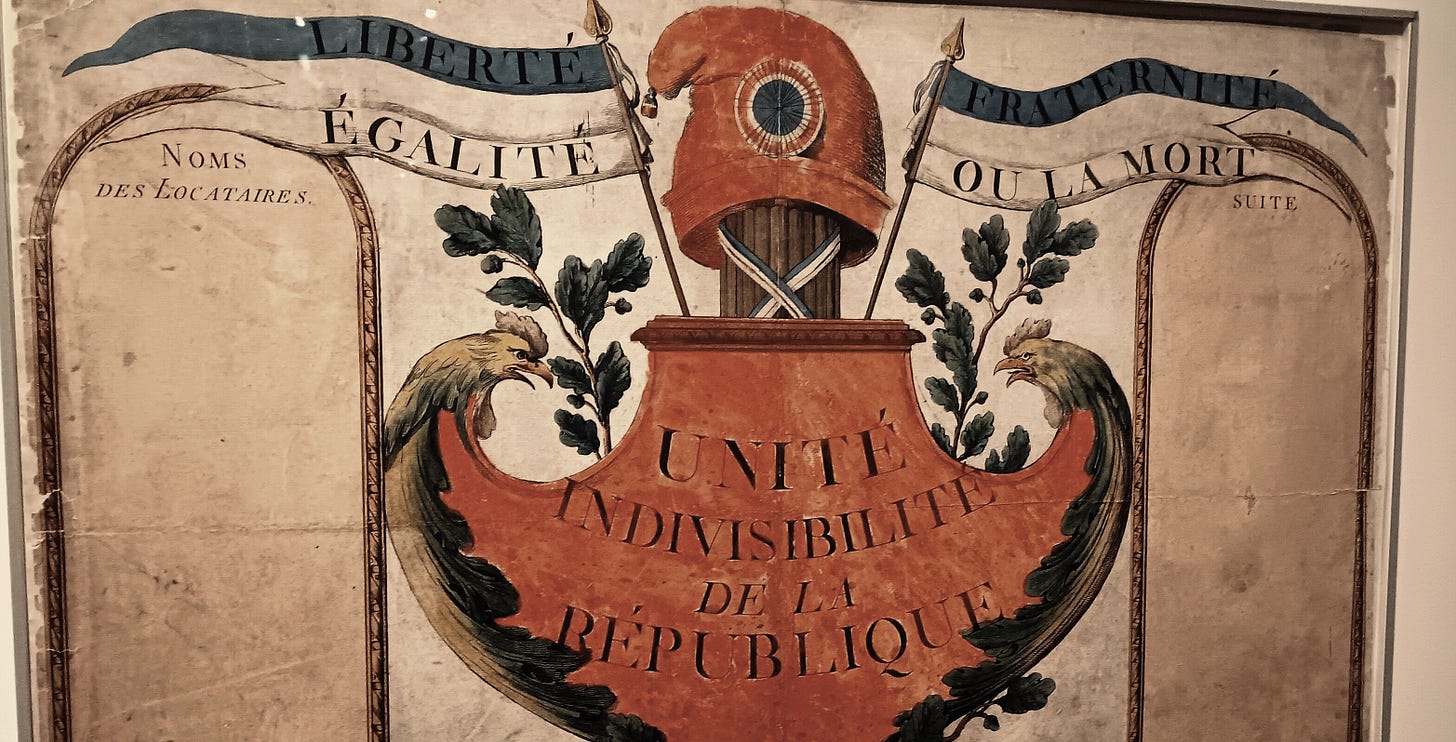

Paris 1793-1794 documents the ensuing chaos from the standpoint of ordinary Parisians – most of whom were helpless bystanders. On display is one of the official boards placed outside Parisian houses, on which landlords listed the names, nicknames, ages and jobs of every tenant (pictured above).

Another striking exhibit is a certificat de civisme (“certificate of public spirit”) issued by the Commune, attesting that the bearer had fulfilled public duties and could not be suspected of counterrevolutionary sympathies. Under the Terror, the panel states, this badge of ideological purity helped avoid detention under the “law of suspects” targeting internal enemies and foreign agents. Other necessary documents for any good Parisian included the carte de sûreté (“safety card”), the forerunner of the identity card, and the certificat de résidence proving that you were not a treacherous émigré.

War and civil unrest, the museum says, served to justify a “new police order” in the city. A key part of revolutionary imagery is the all-seeing “eye of providence”, a masonic symbol adopted by radicals to signal constant vigilance. A “culture of surveillance” developed, with residents expected to join neighbourhood patrols. One painting, entitled Arrests (above), shows a man being picked up for not wearing the obligatory tricolour cockade; another sports the cockade but is asked by watchful citizens to produce his card on account of his aristocratic suit.

Another work by the same artist, Jean-Baptiste Lesueur, illustrates the struggle to keep Paris supplied with food through authoritarian means. A farmer is shown selling grain above the maximum legal price to a “speculator” – but a national guardsman is watching in the background.

Art was used as propaganda in starkly modern ways: joyful, virtuous citizens were depicted at home, at work, or dancing to celebrate their newfound liberty. Not all official art in that era, of course, can be dismissed as trite agitprop. Jacques-Louis David immortalised Montagnard martyrs in such masterpieces as The Death of Marat (1793). He was a friend of Robespierre's who, as a senior member of the Convention, sent many to the guillotine.

David was also the architect of the grand fête de l'Être supreme. As Paris moved to eradicate Christianity, Robespierre promoted the worship of a “Supreme Being”. On June 8, 1794 (or Prairial 20, Year II, in the new calendar set to the birth of the republic, not Christ) the extravaganza involved a parade through the city and a “sacred mountain” erected on the Champ-de-Mars. The creed was short-lived, the curators write, but it “showed how Paris was imagined as the capital of a new civic religion”.

Yet the event marked the beginning of the end for Robespierre. With no royalists left, he could only blame allies for continued hardships. The exhibition does not refer to a long-running, politically charged debate among French historians over whether 1793-1794 was a continuation or a betrayal of 1789. But the curators lean towards the second interpretation by noting that the initial uprising involved the release of a few prisoners seen as victims of despotism; five years later, they add, jails were bursting and the guillotine was “the symbol of the revolution turning against its founding principles”.

Moreover, it notes, 1789 started with a pledge by representatives to write a new constitution while 1793 saw the immediate suspension of constitutional rules. In many ways, the artefacts shown support François Furet's view of the French Revolution as the incubator of twentieth-century totalitarianism. The neighbourhood watches, the state control of the arts and the mass gatherings glorifying the official ideology became hallmarks of Nazism and Communism. The Terror also pioneered death-theme sloganeering: the rallying cry “Liberté égalité fraternité ou la mort”, inscribed on all public buildings by the Paris municipality, evokes the Francoist rallying cry “Viva la muerte” and Cuba's ubiquitous “socialismo o la muerte”.

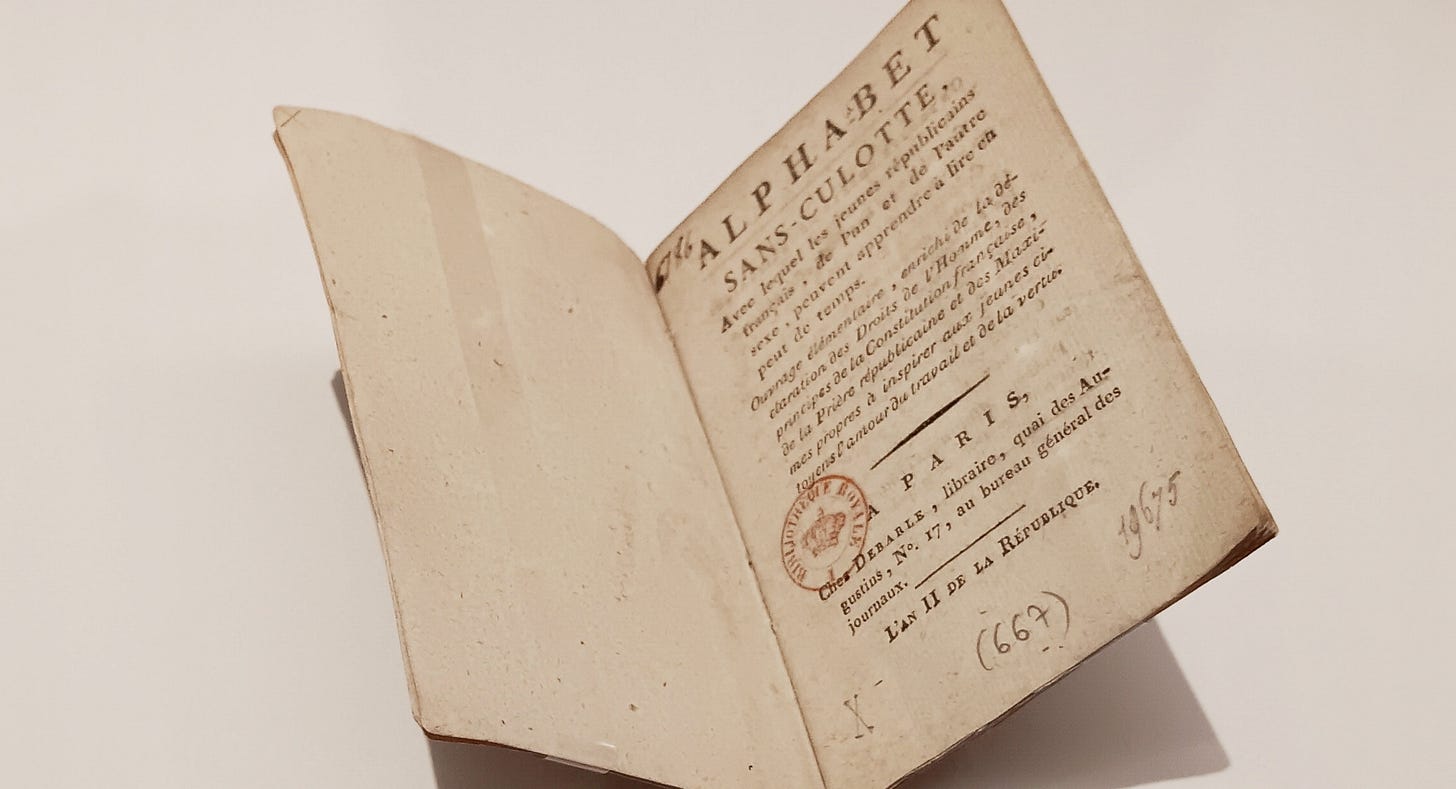

On display is a copy of a booklet entitled Alphabet des Sans-Culottes, a vademecum for any self-respecting revolutionary: Mao's Little Red Book did not originate the concept.

Another harbinger of modern tyrannies is the painting Jean-Jacques Rousseau et les symboles de la Révolution (below). Commissioned in early 1794, it originally featured a portrait of Rousseau flanked by those of Marat and Le Peletier, another hallowed Montagnard. After the collapse of the regime, the painter – a hack named Jeaurat de Bertry – had both erased for the same reason that Trotsky would be airbrushed from Soviet iconography 140 years later.

Robespierre's downfall was swift. He had Danton executed in April 1794, but by that summer the Montagnard strongman found himself in the same predicament his rival had faced. Having been installed as a result of a Parisian insurrection, as a national leader he was alarmed by the capital's claims to supremacy - hence the execution of Froidure and other Commune officers. Robespierre’s ability to turn friends into foes was his undoing: the “incorruptible” never fully controlled the Convention and his purging zeal gave too many people reason to feel threatened. In late July he and his dwindling band of terroristes were sent to the scaffold, in the so-called "Thermidor reaction".

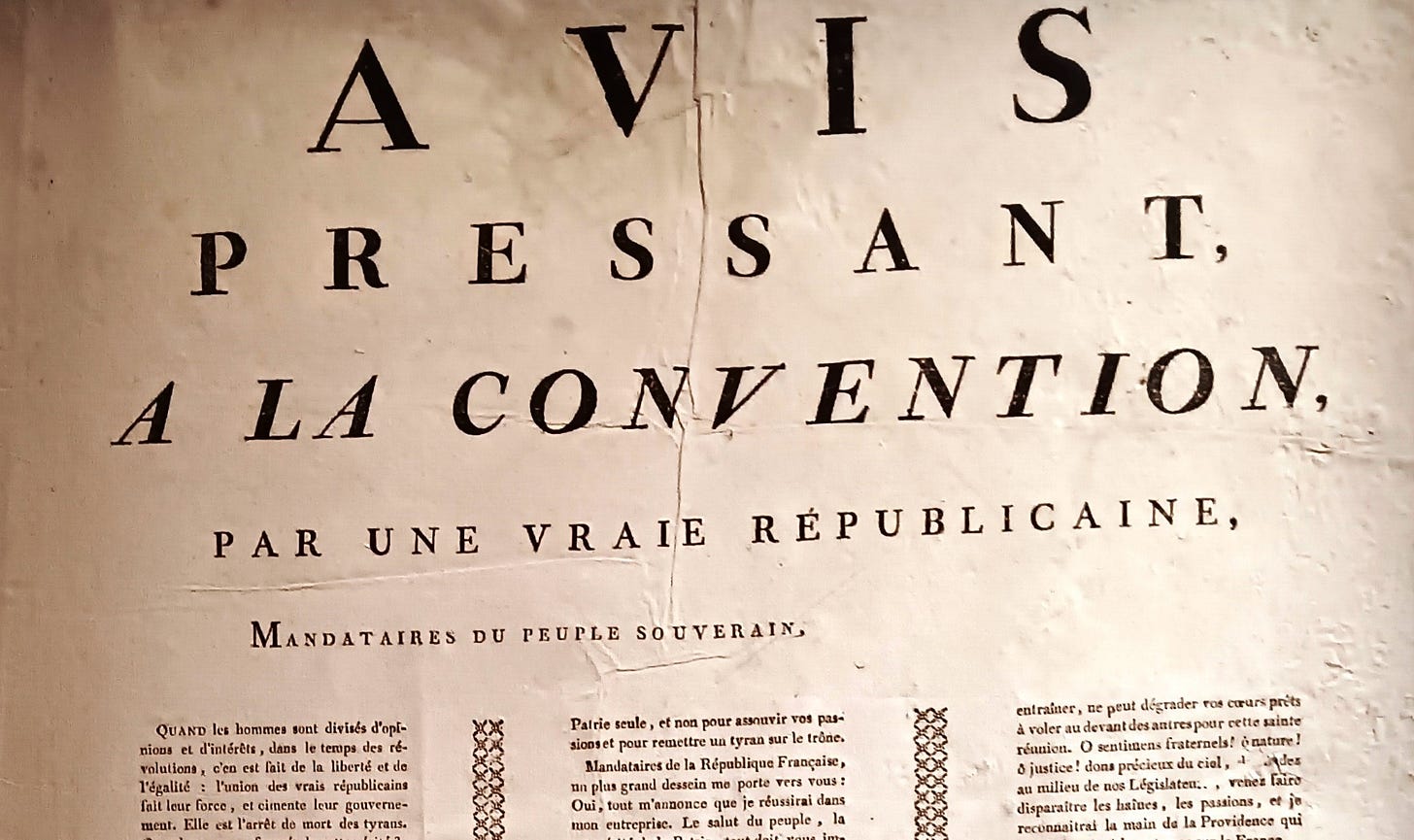

Amid the crescendo of fratricidal struggles, appeals to public opinion became a crucial part of any survival strategy. The exhibition showcases posters put up on Parisian walls by public figures who found themselves in the limelight for the wrong reasons. On one placard, written by David after his incarceration under Thermidor, the artist calls reports of his closeness with Robespierre "outrageous slander". This repudiation – as well as David's renown – probably helped save his skin.

Another eloquent poster on display is a plea by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. The author of Dangerous Liaisons, a Republican moderate, fell out of favour with Parisian enragés just before their takeover. In May 1793, Laclos was accused of taking part in a plot against the Convention hatched at Danton's home. In his response, written from detention, the writer said he had never read such a "stupidly atrocious" accusation, as it was public knowledge that he was already in jail when the alleged meeting took place.

If a poster could save you, it could also cost you your life. One of the most extraordinary figures of the era was Olympe de Gouges, author of the Declaration of the Rights of Women. More than a feminist, she was a humanist who campaigned against slavery. She stood as a lone advocate for reason in fanatical times. Rather that join a faction, De Gouges castigated all of them for tearing the country apart: "Montagne, Plaine, Rolandistes, Brissotins, Girondistes, Robespierrots, Maratistes, infamous labels!" she wrote in March 1793 (above). During the Terror she lived in hiding at her maid's home in Paris but refused to be silenced. De Gouges was arrested for posting a placard condemning the Montagnards and was guillotined in November 1793.

The year-long Parisian phase of the revolution has cast a long shadow. Thermidorian leaders abolished the mayor’s office and broke up the city into arrondissements. The Commune was briefly revived following upheavals in 1848 and 1871, but in both cases the challenges it posed to the national legislature quickly led to its suppression.

It was not until the late twentieth century that the French state trusted Paris with its own administration again. By then the city’s radical populace had been edged out. Nowadays its genteel residents and smart shops are less likely to be the originators than the victims of revolutionary outbursts – whether at the hands of yellow-vested populists or youths from impoverished ethnic suburbs.